Challenging Students to Find Connections Between Picture Books

/When you’re focusing on a picture book unit study, it can be tempting to focus on that book alone. But don’t forget to help your students to step back and make the connections with other picture books - and to share those connections with others.

It’s important when we’re teaching reading that we help students to make text-to-text connections with other pieces of text. This is particularly important as students get older and begin to find references to other books in the novels they are reading or need to collect information from a range of sources to write an informational report, but it’s a skill which helps students learn and develop their schema from the youngest grades at school.

When students are reading picture books, you can start with the easiest connections. Students can identify some of the basic elements of the book - like it’s a book about school, a book about animals or a book about space. Students can identify other books they know which also have this element. This allows them to identify differences and similarities as well as identifying what those books tell them about that topic.

Easy connections can also be made when students are exploring texts in a series of books or picture books written by the same author. The Pig the Pug books, for example, all include the same two characters as well as similarities in what those characters do (Pug does the wrong thing, Trevor does the right thing). Students can connect the books easily through the characters and the similarities, then use that information to look deeper at the differences in the books - what does Pig do wrong in this book? How is it different to what he does wrong in that book?

Once students have developed the easy connections, they can start looking for more difficult connections. You can assist them in this by offering students two or more books which aren’t obviously related and asking them to find the similarities between the books. This can be even more fun to do if you haven’t found the connections yourself - you might be surprised what the students will present you with when you’re not guiding them in a certain direction.

Another way to do this is by asking students to look for certain themes or characteristics as they explore books over a period of time. You might ask them to look for lost things or characters who are anxious about something or books with surprise endings. When students begin to find these connections, they can look at how the author and illustrator has portrayed that particular element or theme, gaining a better understanding of how a book can be crafted to get a response from the reader.

How Can Students Share the Connections They Make?

The easiest way for students to share the connections between different texts is simply by talking about them with their peers or in student conferences. You can make this easier for students by providing prompts in the room - a question on the classroom wall which asks students how books connect to each other can help it become a normal part of conversation about books.

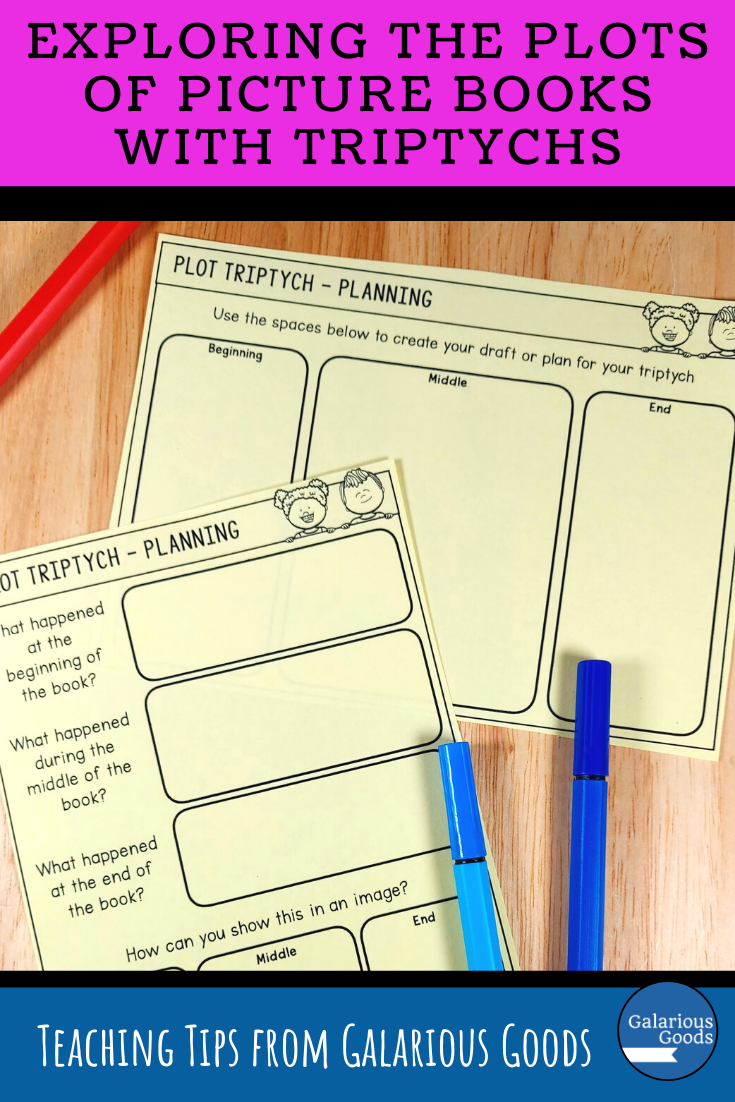

Students can also use graphic organizers to make connections between different book - either by using prepared ones or making their own.

When you’re working as a class on a bigger project, you can work with your students to create a display showing the connections you’ve made as a class. This might be a bulletin board within the classroom, a display in the school library or office or even an online display which can be shared with parents and other students in the school.

Students can also share their connections with their ‘future self’ by keeping a reader’s notebook. Taking some time to go back through old entries can remind students of the connections they made back then - and allow them to make new connections with books they’ve read since then.