Explore the Pig the Pug Series with these Writing Tasks

/We’ve talked about how we love the Pig the Pug series by Aaron Blabey before - and how it can be used in the classroom. But how can we use it to teach writing? These five writing tasks allow you and your students to take a closer look at the books, and a range of writing formats

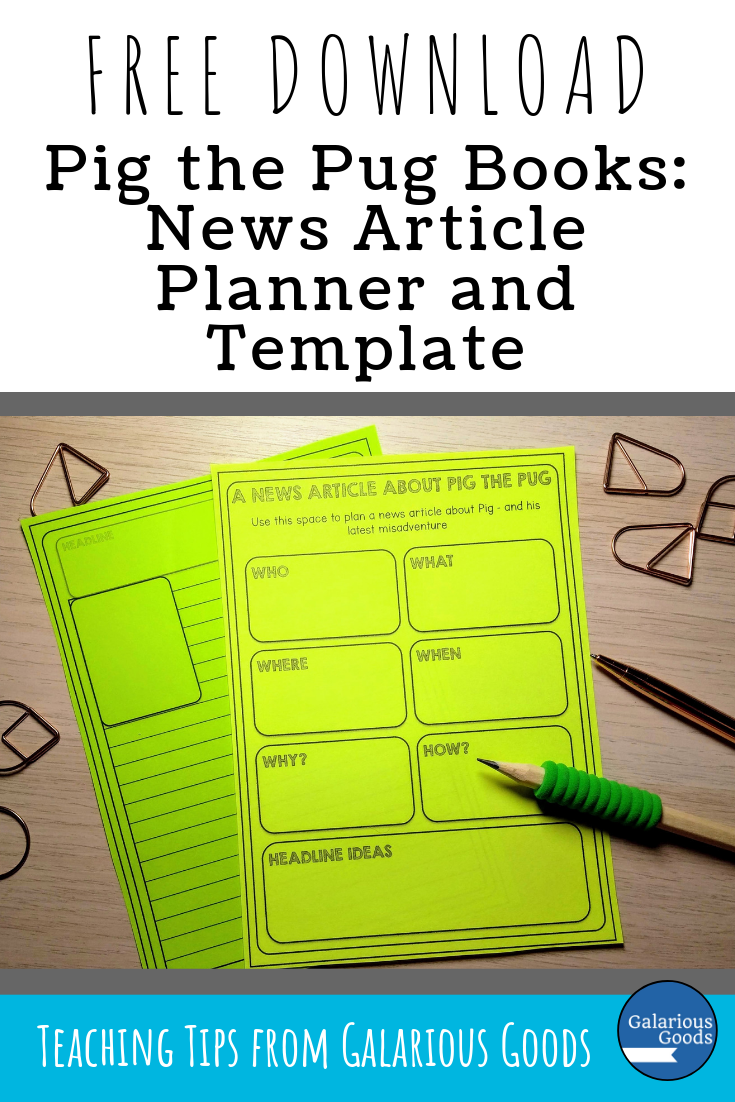

1. Write a News Article About Pig’s ‘Adventures’

When Pig the Pug goes big, it’s usually followed by some sort of disaster. This is bad for Pig, but great for budding news article writers.

Writing a news article is a great task for a range of grades. For younger students who may be just learning about the format, it’s a great way to identify the ‘who, what, where, when and why’ - good reading questions - before participating in a shared writing of an article as a small group or a whole class. Students can follow this shared writing about one of the Pig stories with individual or paired writing about one of the other Pig stories.

For older students, the Pig books offer a great story to write their article about. They can report on the time that Pig ‘flew’ out the window (plenty of headline opportunities there - another aspect you can explore with the class) or the time he exploded a bathroom just because he preferred to be dirty.

2. Write a Diary Entry - or a Series of Diary Entries

What is Pig thinking? While that’s a slightly scary thought, it’s also a great way to explore the Pig the Pug books through writing.

You could ask your students to write one diary entry - focusing on the aftermath of an event perhaps, or what Pig is thinking before disaster strikes. Or you could ask your students to write a series of diary entries which explore the entire events of the week. What is Pig thinking about as he participates in the photo shoot and thinks of himself as a star?

Or - to change it up a little - what exactly is Trevor thinking? What would his diary entries look like after a big Pig Event or in the lead up to one.

This is a great activity to pair with diary led books like the Diary of a Wombat series by Jackie French or the My Australian Story books for older students. Students can look at the examples of diary entries and identify the elements of them before applying these ideas to their own writing.

3. Write a Comic Strip

How can you condense all - or a good part of - a story into just a few small boxes? This is the question which faces students when you ask them to create a comic strip of on of the Pig the Pug books.

Students can talk about which are the most important parts of the story, creating a list which allows them to create 4 or 5 panels of a comic. They can then explore what images or words they could fit into that comic strip.

Students can also explore whether they should keep Pig looking like the Pig of the books, or whether they should explore their own style of drawing in their comic strip - and why they might make some changes.

This is a great way to explore retell and main idea with your students - particularly those in middle to upper primary classes.

4. Review of the Book

Writing a good book review can be a great way to get other people to enjoy the books you enjoy. The Pig the Pug books are great for reviews because there’s usually a range of reasons why readers love them.

Students can explore a range of book reviews from different places before they write their own. You can also share write a review with the whole class before students head off to write their own reviews.

Some things students can concentrate on in reviews is comparing them with other books (maybe other books about dogs, other books which feature animals or other funny books) or focusing on why they are so enjoyable to read.

If your students didn’t enjoy the book, they can also write a review highlighting why. (This can be a great activity even if your students did enjoy it - what kind of review would you write if you didn’t?)

5. Podcast Episode

Podcasts are really popular, with a number of podcasts created just for children. You and your students could listen to some of them before getting into creating your own.

Successful podcasts have a question or a theme to work through. When it comes to Pig the Pug they might like to discuss why they enjoy a particular book, which Pig the Pug book is the best, what it would be like to own a dog like Pig or what to read after you’ve finished all the Pig books.

Students should write at least an outline before they start recording their podcast. If they’re working in a pair or small group, they might identify different parts to talk about or create a list of ‘talking points’ to tackle together. If they’re working on their own they might like to create a whole speech to write about.